“Doubt is the greatest gift given to mankind.” The Raja of Mahmudabad said this to me during one of our conversations. “Otherwise our minds would all be in stasis.”

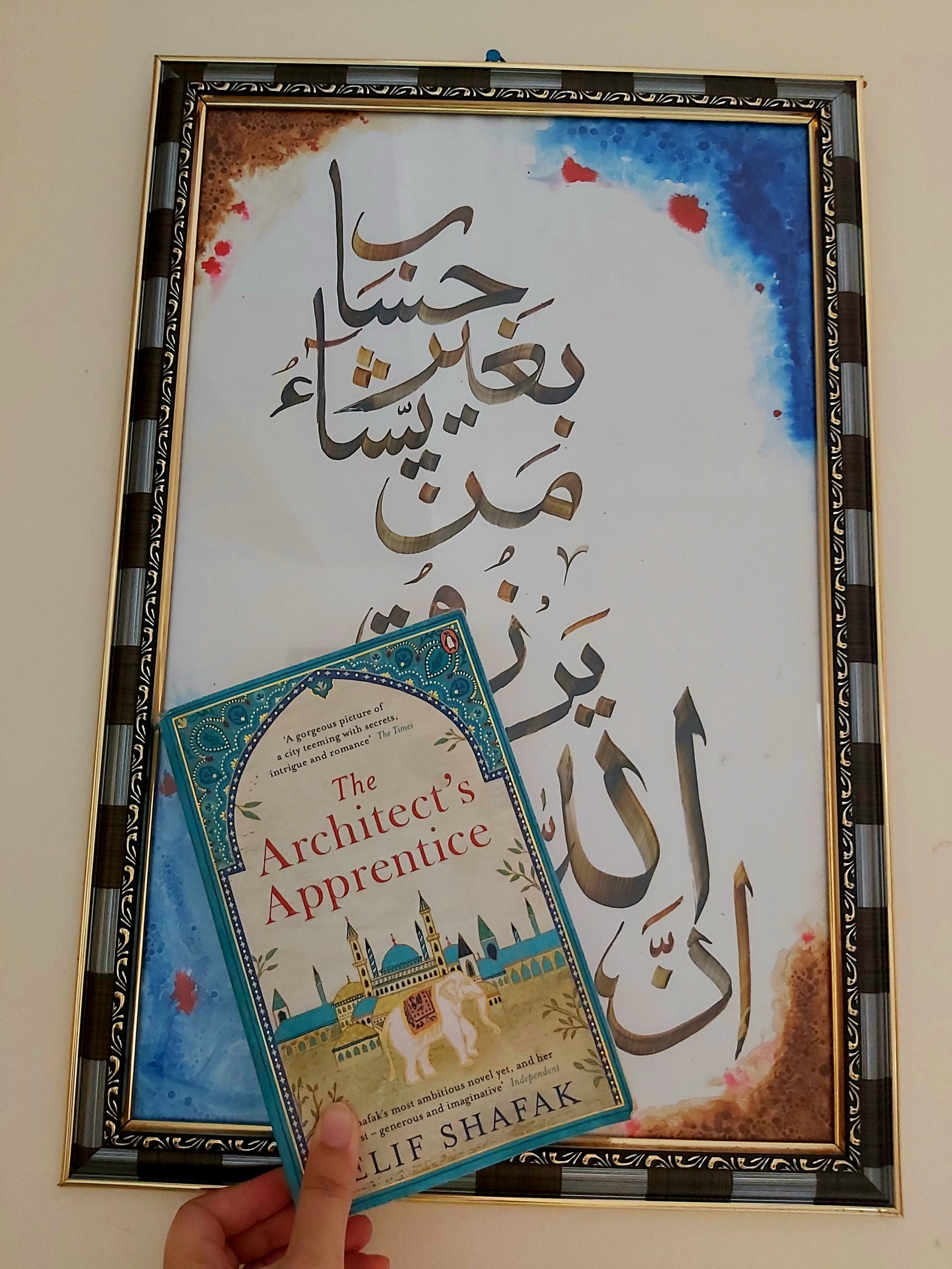

The Architect’s Apprentice is a book for doubters.

People who wonder if there is any order or sense to this world. People who are consumed by their own questions, and have no one to give them the answers.

This book is for people who, like its protagonist Jahan, are looking around in bewilderment, unable to find direction. People who feel … lost. With a hollow absence within them, an aching for… they know not what.

Because a great gift is also, very often, a great curse.

At least that’s how it feels to me nearly every day of my life. The greatest curse of my life is that I cannot stop asking questions. I cannot stop having doubts. I cannot stop having faith, either—and that is why I forever burn in purgatory, neither here nor there.

And then, along comes this book that says:

‘Little did he know, back then, that the worth of one’s faith depended not on how solid and strong it was, but on how many times one would lose it and still be able to get it back.’

This turquoise-covered book, so elegant and enchanting, mentions at one place, in a very subtle and understated manner, St Thomas who was ‘a doubter’. He doubted everything. Could not help it. But God loved him just the same.’

Of one thing then, I had no doubt. This book was a gift from the heavens for me, the perpetual doubter. God loved me, too, just the same.

St Thomas was the patron saint of ‘carpenters, builders, architects and construction workers.’ Craftspeople. Creators. Artists. Close enough, I suppose, to wordsmiths and those who constructed and crafted entire cities through words. St Thomas could be my patron saint too.

Elif Shafak’s book is a rich, vivid description of life in the Ottoman Empire, viewed through the eyes of Jahan the elephant tamer who becomes the Royal Architect’s apprentice through a twist of fate. And falls in love with someone he can never ‘be with’: the princess Mihrimah herself.

The sheer beauty of the ‘dedication’ that this book begins with, is a sign of the bedazzlement that awaits the reader inside.

‘For apprentices everywhere—no one told us that love was the hardest craft to master.’

Indeed. Oh, indeed.

This book speaks of Master Craftsmen—and Craftswomen—builders of marvellous wonders of architecture. Masterpieces of human endeavour. The book itself is one such Masterpiece. Every line crafted with great care, but none more so than the very first page which is the embodiment of perfection.

Of all the best opening lines in the novels I have read, this is the only one that gave me goosebumps.

‘Of all the people God created and Sheitan led astray, only a few have discovered the Centre of the Universe.’

A place that is supposed to be devoid of good and evil, past and future, you and I. A place only of endless calm. But these few who discovered that place were so struck by its beauty that they lost the ability to speak. And then the angels took pity on them, and gave them a strange deal.

‘So the handful who stumbled upon that secret location, unmarked on any map, returned either with a sense of longing for something, they knew not what, or with myriads of questions to ask. Those who yearned for completeness would be called ‘the lovers’, and those who aspired to knowledge ‘the learners’.

It is the particular gift and curse of my life that I am not one of these. In fact, I am both.

The lover and the learner. Always both. Not alternately—but at the same time.

I wonder what strange curse the angels cast on me.

‘This nobody knows, but at the bottom of one of the hundreds of buildings that my master built rests the centre of the universe.’ If ever there was a line that could elicit goosebumps not just the first time it was read, but every time that it was read—it is this.

At its heart the book is quintessentially Shafak— a Sufi story underneath the surface of palace intrigues. Full of subtle mystical observations, deep musings on faith and the human spirit. And questions, glorious questions challenging the dogmatic understanding of religion. Questions that echoed every call of my heart.

These lines for instance, spoken by the sufi Majnun Shaykh who is being tried for heresy.

‘Is it true that you have said you have no fear of God?’

‘Why should I fear my Beloved? Do you fear your loved ones?’

A murmur rose from the crowd. Someone shouted ‘Silence!’

‘So you accept that you have claimed to resemble God.’

‘You think God is similar to you. Angry, rigid, eager for revenge… Whereas I say: instead of believing that the worst in humans can be found in God, believe that the best in God can be found in humans.’

Yes, have we not been created in the image of the Divine! How long have I yearned for this understanding of religion, in which everything is not related to punishment and incurring divine wrath—in which the highest and most important concept is the concept of Divine Mercy and Divine Love.

In another instance, when Jahan, along with his elephant, is accompanying the troops to the battlefield, a soldier says to him: For every dastard’s head you get a mansion in heaven.

‘Not knowing much about Paradise and why he would need houses there, Jahan kept quiet.’

Why indeed!

What do people need houses for? We need houses as places of safety and refuge, sanctums of peace and protection from the world outside.

From what would one need protection in Paradise!

If Paradise is a place where every space is filled with peace and safety and harmony and love, of what use would be a house? If Paradise is a place where we cannot be hurt or fall ill or die, then every space in it would be a place of refuge. We might sleep near the waves of the ocean or over the blades of grass in a meadow. We might sit and write under the moonlit night on the snow clad slopes of the Paradisiacal Mount Everest. Why indeed would we need a house?

The book thus follows the questions and confusions of Jahan, his desires and ambitions, the yearnings of his heart.

It seemed to speak to me not only of my religious confusions, but also of my ambitions as a writer, a craftswoman practicing her craft.

‘If not put to use, iron rusts, woodwork crumbles, man errs, Sinan said. Work, we must.’

‘He had reached a point in his craft where he could either improve or destroy his talent. Dawud, Yusuf, Nikola—these were not his rivals. His most fearsome rival was himself.’

It was a reminder to me that I needed to keep going, pen to paper, head low to the desk. I needed to master my craft. I needed to grow and to evolve, to stop myself from turning to rust.

‘You build with wood, stone, iron. You also build with absence.’

Much did I build with my father’s absence. Much did I build with unspoken absences.

Then at one point, Jahan realises why Master Sinan the Chief Architect, chose him as one of his apprentices.

‘You do not choose the finest. You go for the ones who are good but are… ’ He halted, searching for the word. ‘Lost… abandoned… forsaken…’

Did that mean, perhaps, that I was the chosen one? I could have no illusions ever of being the finest—but I did know certainly that I was… lost.

‘Have you ever seen sea turtles washed ashore? They keep walking with all their might but the route is a wrong one. They need a hand to turn them back towards the sea, where they belong.’

So this is what it was. Throughout this journey, the journey of the reading dervish, I was being consistently turned back towards the shore, like a lost sea turtle. The turtle whose instinct pulled it towards the sea, but it often lost its way. And every now and then, a hand came to put it right back on the path. Put me right back on the path. The path to the vast mystical sea where I belong.

And the book spoke of love.

Jahan’s unending, unfulfilled, unspoken love for the princess Mihrimah. Unfulfiled—yet not really. It is a love that is there and yet not there. That is known and yet not known. That is reciprocated and yet not reciprocated.

Jahan constructs an entire mosque peppered with symbols of his love.

‘At no stage did he confess to himself that he wanted the mosque to remind Mihrimah of the day they had met.’

‘In his plans he chose the lightest marble and granite for the columns, the colour of her dress and veil. Four towers would support the dome, as they had been four in the garden that afternoon: the Princess, Hesna Khatun, the mahout and the elephant. And a single minaret would stand high, slender and graceful, just like her. Her mosque would have lots of windows, both on the dome and in the prayer hall, to reflect the sunshine in her hair.’

Such is the depth of a love that is spiritual in its nature—transcending the physical and material trappings of male-female attraction. A love that turns to worship. A beloved who is made eternal through her/his reflection in the lover’s craft.

For an artist, the art is both love and worship. And that is why her work shall always be embedded with the presence of her beloved.

Much as Jahan embedded his final and most wondrous construction with an unnoticeable detail that spoke of Mihrimah. That marvellous Wonder constructed by him stands in our very own country—India—but I cannot speak more of it without giving away the book’s ending.

This ought to be where I wrap up this piece—but there is more. More of love. For there are different kinds of love.

The other pure love whose thread runs throughout the book is between the tamer and his elephant. Jahan and Chhota. For it is not for Mihrimah, but for Chhota, that Jahan feels this:

‘Centre of the Universe was neither in the East, nor in the West. It was where one surrendered to love. Sometimes it was where one buried a loved one.’

But the burial may be in the earth, or it may sometimes be a burial inside the earth of your heart.

So many different loves has the human heart. And yet all end in loss. Why? Why must the heart be broken so? Why must we be submerged in pain?

Master Sinan answers from the pages of the book:

‘Sometimes, for the soul to thrive, the heart needs to be broken, son.’

Great post 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike

Beautifully written review…I shall read this book! Amazingly, I came across your post randomly, wanting to read some poetry, and it caught my eye…and then to read about a Master Builder…having wrote a poem of that same title, just a day or so ago…Well, the craft and path beckons! Thank you for your wonderful insights Zehra, Salaam!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading and appreciating. I am glad it resonates with you!

LikeLiked by 1 person